The reason why tail docking is still a routine at many pig farms is the consensus that it is still the most effective solution to prevent tail biting. It’s the result of a complex and multifactorial problem.

Routine tail docking: a ban since 1994

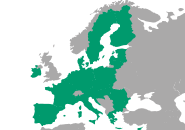

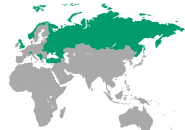

In 1994 already, legislation was passed to ban routine tail docking of piglets in Europe. Since then, the legislation has been amended several times and was substantially updated by Directive 120/2008/EC (‘ the Pig Directive’) that specifies the measures that must be undertaken before a farmer can resort to tail docking (such as stocking density, and providing specific enrichment materials). But despite this regulation, “tail docking” is still a routine practice on many pig farms in Europe. There are a few exceptions though. In Finland and Sweden, due to stricter national rules compared to EU legislation, tail docking is no longer allowed. In Norway and Switzerland, less than 5% of pigs are tail-docked.

Tail biting: a welfare and economic cost

To improve social acceptance of pig production and further improve animal health, welfare and work pleasure for farmers, we should move away from tail docking. The main reason why tail docking is still a routine at many pig farms is the consensus that it is still the most effective solution to prevent tail biting. Tail biting is not only detrimental to animal welfare, it also carries an economic cost. Tail biting can be classified into two groups: the pre-injury stage, before any wound on the tail is present, and the injury stage, where the tail is wounded and bleeding. The infections and lesions can cause carcass condemnations at slaughter and can even lead to mortality in severe cases. Research from the UK showed that tail biting can lead to a profit loss of 43% per pig, as a result of losses attributable to carcass condemnations and trimmings .

The main risk factors for tail biting behaviour

Tail biting is a complex and multifactorial problem. The precise etiology of tail biting behaviour is unknown, and many other risk factors besides housing related issues have been identified.

The main risk factors for tail biting are:

- Lack of enrichment material and barren floors

- Poor ventilation, temperature fluctuations, high level of ammonia

- High stocking density and large herd

- Gastrointestinal discomfort

- Poor health status

- Suboptimal or imbalanced diet

- Individual factors (age, genetic).

Enrichment material and its costs

The provision of enrichment material in the form of straw, chains or toys is one of the most practical and powerful environmental tools to prevent or minimise tail biting. Since 2003, the provision of appropriate environmental enrichment to pigs of all ages has been mandatory across the European Union. A report from the European Commission showed that enrichment material represents only 0.25% of costs on fattening farms in Sweden and 2.8-4% for breeding units. In Switzerland, the expenditure on rolls of compressed wheat chaff was around 0.90 Euro per fattening pig. Finland and Sweden stopped routine tail docking completely and have an average production cost of 1.66 Euro and 1.63 Euro per kg hot carcass weight , which are not even the highest in the EU.

Effect of more space per pig

Also the space per pig (stocking density) has an effect on aggression and tail biting. German research showed that the incidence of tail lesions was higher in undocked pigs raised in a conventional system, where the pigs were regrouped and transferred to conventional finishing pens at ten weeks of age compared to undocked pigs from a wean-to-finish system, where the pigs remained in their pens until slaughter with higher space allowance during rearing. Other research confirmed that the reduction of stocking density modified the pigs behaviors and reduced the fecal corticosteroids levels, highlighting an improvement of welfare conditions .

Although both enrichment material and stocking density are important strategies, it cannot itself eradicate tail biting behavior. The variability of responses to the different solutions usually proposed highlights the individual dimension of this deviant behaviour. It is therefore also the capacity of individuals to adapt to the proposed breeding conditions that is questioned, and not only these conditions.

In the 2nd part of this article we look at stress management.