In the previous article on tail docking we addressed the risk factors that increase tail biting, including bad ventilation, boredom, poor health, high stocking densities and more. The risk factors are a combination of environmental (management) based risk factors and animal related factors. The common denominator and solution of all these risk factors is stress reduction.

Stress management: the key to end tail docking

Tail-biting is caused by stress and as causes more stress, as indicated by both behavioural and physiological changes in the animal’s body. Stress is experienced by both the pigs that are bitten (the victims), but also the biters. Then biting spreads through a farm like a contagious disease. This deviant behaviour is a behavioural pathology due to stress. The “big biters” are the first animals to succumb to this pathology. This aggressive behaviour with their congeners leads to a level of stress that makes them sick in their turn.

As presented by Selye, stress is a response to external factors. Think of regrouping, weaning and transfer of the animals. Stress can also be induced by increased competition for feed and water when pens are overstocked. All of this stress destabilizes animal comfort. As a consequence, the animal will adapt its behaviour (aggressivity, sign of discomfort) in a quest to find its comfort zone again. Most of the time, stressors stop and animals return to their normal behaviour. However, stressors can also continue and animals enter a phase where they are not able to handle the stress anymore. As a consequence, distorted behavior develops and can lead to diseases, abnormal behaviour such as tail biting or other problems. Stress should therefore always be prevented.

Selective breeding and piglet socialization

Not all pigs are equally sensitive to stress factors and start to bite pen mates. Research showed that Duroc pigs are more active and investigatory than Landrace and Large White pigs, performing more biting of pen mates. Other research groups found tail-biting to be heritable in Landrace, but not heritable in Large White pigs. They also found that in the Landrace population, tail-biting was unfavourably genetically correlated with leanness and back fat thickness at 90kg. The researchers mention the possibility to develop a selection index to reduce the predisposition to exhibit tail-biting behaviour through selective breeding. It is also suggested that management before weaning can also help in reducing stress. Research showed that cross-fostering and socialization early in life reduces the later occurrence of aggressive biting. The researchers therefore state that the possibility for piglets from different litters to interact from the second week of age should be encouraged. The use of familiar odours can also reduce stress when pigs are moved from one stage of production to another.

Going for a successful ban of tail docking

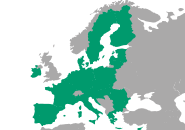

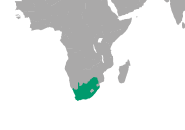

Sweden and Finland managed to raise pigs without tail docking. These countries strongly focus on the use of enrichment materials (often straw), reduced stocking rates and high standards in relation to thermal comfort and air quality, health status, competition for food and space, and diet. Being able to end routine tail docking in more countries requires government strategies per country and an evaluation of current commercial rearing conditions. And this may have a price. The government, farmer and consumer are all responsible to end routine tail docking. Three EU Member States – Austria, Denmark and Slovenia – have specific legislation further limiting this practice. The Netherlands spoke out and said it wants to end this practice by 2030. Other European countries have not mentioned a deadline (yet).

Also have a look at part 1 of this article: Tail docking part 1: A practice from the past, at last?