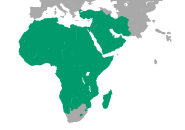

Each of us is concerned about “animal welfare” and feels able to judge (without much legitimacy) the conditions in which animals are raised! These issues of public interest are pushing industry professionals to create new quality channels. In France, for example, there is “La Nouvelle Agriculture” by Terrena or “Oui c’est bon” by LDC. Other players, such as the Casino group in the mass retail sector, are joining the animal welfare labelling approach by giving their products an A, B, C or D mark. These approaches are not limited to France, a lot of countries have their own labelling systems. The most advanced species in these quality approaches is poultry, with numerous quality channels and more than 24% of poultry sold under the label.

While these new approaches are flourishing, only one point of view persists in the elaboration of the specifications: the human point of view! But what about our main stakeholder? This two-legged gallinaceous animal that everyone forgets to ask for its opinion?

Ask the hen what she thinks about well-being at work!

What may seem good to us is not necessarily good to a hen! The vast majority of poultry, for example, prefer to stay in a building rather than in an open-air run without trees. Indeed, from their point of view, the building provides protection against predators, which is logical, you might say, but you should have thought about it! It is therefore very important not to confuse societal expectations: the desire to see a hen outdoors and animal welfare: a feeling of protection among others. It’s all a question of perception and not being a hen it’s not always easy to know what’s good for it!

Fortunately, behavioural professionals called ethologists are able to put animals in situations where they can express their needs or preferences in terms of comfort and well-being. The answers provided by the animals are sometimes confusing, as shown by the work of Faure and Mills (1995). Animal welfare standards are based on this work, but remain largely a reflection of societal demand. However, the farmer in his building is able to see if his animals show signs of discomfort and to remedy this accordingly. Isn’t observation common to both professions?

Several symptoms may indicate a decrease in welfare in poultry:

– Neck feather loss

– Decreased appetite

– Alterations: scratches, feather pecking

– Poultry very agitated or totally apathetic

– ….

You should be particularly attentive to the appearance of these signs because the longer you wait, the more irreversible the damage will be. In this area, as with health in general, it will be difficult to “cure” your poultry, so prevention remains your best asset.

If we want to meet this societal demand, we must consider animal welfare as synonymous with the absence of unnecessary stress. This raises the question of the compatibility between reducing stress (e.g. density) and the productivity of the farm.

Animal welfare and animal husbandry: is it compatible?

The environment contains many barriers to well-being

Stresses in animal husbandry as a barrier to the animal’s well-being are very varied. We are talking about stress here because the nature of stress is diverse. We think first of all of oxidative stress, which is certainly real but too often cited to the detriment of other types of stress. We are left with thermal stress which has a great impact but which remains periodic, inflammatory stress which is in reality the degraded evolution of oxidative stress and we are left with this last stress which is difficult to classify but which everyone feels: psychosocial stress! You know this famous stress that the breeder describes as a state of uneasiness that he feels in his animals? My chickens are nervous today”, “My chickens don’t eat as they should””, “My chickens don’t eat as they should”, “My chickens don’t eat as they should”.

This stress is difficult to measure and yet the causes are well known:

– Change of building

– Transport

– Handling: vaccination

– Density

– Grouping of animals

Despite good control of these stressful factors, the behaviours observed in response to these factors are variable.

Collective or individual response?

Some genetics are known to be more sensitive to stress than others. However, in the same building it appears that the response to stress in poultry is variable, their response is individual!

Sensitivity to stress is therefore individual and has 2 components:

– The genotype: difficult for the farmer to control.

– The phenotype: depends on the experience of the poultry, how to deal with it? The most common error is to consider that all the individuals in the flock will react unanimously.

Illustration of a difference in individual response to the same stressor.

The right approach to improving poultry welfare

Adopt global stress management

As mentioned above, the response to stress in animals is individual and partly related to the poultry’s experience. Limiting the sources of stress therefore seems to be the first thing to do. Conventional stress management techniques such as reducing transport time, reducing handling or reducing density are essential but limited by the productivity of the farm. Another point on which welfare specialists are working is the enrichment of the animals’ living environment. The latter has become poorer with the industrialisation of the sector and is no longer in line with the expectations of the welfare quality sector.

Enrichment, the key to a thriving animal?

Poultry need to express natural behaviours such as pecking, scratching and grooming. These actions will enable them to feel better through the dopamine production they generate and thus contribute to their well-being.

To encourage these natural behaviours, enrichments have been developed on the farms. The most common are strings, alfalfa bales and pecking blocks. However, farmers observe that not all poultry use them. The notion of individual response still predominates here. Moreover, it seems that the effect of these enrichments is not sustainable.

Essential oils, for an animal that feels good in its skin!

Our olfactory solution based on a unique extract of orange essential oil has proven to be very effective in reducing stress in poultry and ultimately improving their welfare. Its effect is purely cerebral. It strengthens the animal mentally by increasing the flow of positive messengers at the level of the neurotransmitters involved in the response to stress. This enables animals to adapt more easily and for longer periods of time to stressful situations but, above all, it offers the possibility of an individualised response while maintaining natural behaviour: the animal chooses to do what is best for it at the moment.

Furthermore, the breeders have noticed that in the presence of these olfactory solution, poultry maintain a marked interest in enrichment for several weeks. In fact, by reducing stress in their poultry, they manage to maintain a natural exploration behaviour by exploiting the enrichments, which will have the effect of providing a feeling of well-being through the production of dopamine: the circle is complete!

Stress management in poultry is complex. Only a global approach to the animal can significantly reduce stress and its consequences on animal performance and thus lead to better-being.